The Operator Pattern from Kubernetes is an excellent way of handling tasks in a cluster in an automated way, for example, provisioning applications, running backups, requesting certificates, and injecting chaos testing.

As a Nomad user, I wanted to do something similar for my clusters, so I set about seeing how it would be possible. It turns out; it is much easier than I expected! While Nomad doesn’t support the idea of Custom Resource Definitions, we can achieve an operator by utilising a regular Nomad job and the nomad HTTP API.

The Setup

We’re going to build an automated backup operator! We’ll use the Nomad Streaming API to watch for jobs being registered and deregistered. If a job has some metadata for auto backup, we’ll create (or update) a backup job. If a job is deregistered or doesn’t have any auto backup metadata, we’ll try to delete a backup job if it exists.

The complete source code is available in the Nomad-Operator repo on my GitHub.

Consuming the Nomad Streaming API

The Nomad Go API library makes it easy to consume the streaming API, handling all the details, such as deserialisation for us.

The client is created with no additional parameters, as the Address and SecretID will be populated from environment variables automatically (NOMAD_ADDR and NOMAD_TOKEN respectively):

client, err := api.NewClient(&api.Config{})

if err != nil {

return err

}

As we want to only listen to jobs that have been modified after our application deploys, we need to query what the current job index is at startup:

var index uint64 = 0

if _, meta, err := client.Jobs().List(nil); err == nil {

index = meta.LastIndex

}

Next, we use the EventStream API and subscribe to all job event types (in practice, this means JobRegistered, JobDeregistered, and JobBatchDeregistered):

topics := map[api.Topic][]string{

api.TopicJob: {"*"},

}

eventsClient := client.EventStream()

eventCh, err := eventsClient.Stream(ctx, topics, index, &api.QueryOptions{})

if err != nil {

return err

}

The Stream(...) call itself returns a channel which we can loop over forever consuming events, ignoring the heartbeat events:

for {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return nil

case event := <-eventCh:

if event.IsHeartbeat() {

continue

}

c.handleEvent(event)

}

}

Finally, this operator only cares about jobs being registered and deregistered, so we loop through all the events and only handle the JobRegistered and JobDeregistered events:

for _, e := range event.Events {

if e.Type != "JobRegistered" && e.Type != "JobDeregistered" {

return

}

job, err := e.Job()

if err != nil {

return

}

c.onJob(e.Type, job)

}

Handling Jobs

When we see jobs, we need to handle a few different cases:

- Jobs which are backup jobs themselves should be ignored

- Jobs without backup settings should have their backup job removed (if it exists)

- Jobs with backup settings should have their job created (or updated if it exists)

- Deregistered jobs should have their backup job removed (if it exists)

We’re using the job level meta stanza in the .nomad files for our settings, which looks something like this:

task "server" {

meta {

auto-backup = true

backup-schedule = "@daily"

backup-target-db = "postgres"

}

}

func (b *Backup) OnJob(eventType string, job *api.Job) {

if strings.HasPrefix(*job.ID, "backup-") {

return

}

backupID := "backup-" + *job.ID

settings, enabled := b.parseMeta(job.Meta)

if eventType == "JobDeregistered" {

b.tryRemoveBackupJob(backupID)

return

}

if !enabled {

b.tryRemoveBackupJob(backupID)

return

}

b.createBackupJob(backupID, settings)

}

Attempting to remove the job is straightforward as we don’t care if it fails - it could be that the job doesn’t exist, or is already stopped, or any other number of reasons, so we can use the Deregister() call and discard the output:

func (b *Backup) tryRemoveBackupJob(jobID string) {

b.client.Jobs().Deregister(jobID, false, &api.WriteOptions{})

}

Creating the backup job involves rendering a go template of the nomad file we will use, and then calling Register to submit the job to Nomad. We’re using the fact that our backup IDs are stable, so re-running the same backup ID will replace the job with a new version.

func (b *Backup) createBackupJob(id string, s settings) error {

t, err := template.New("").Delims("[[", "]]").Parse(backupHcl)

if err != nil {

return err

}

var buffer bytes.Buffer

if err := t.Execute(&buffer, s); err != nil {

return err

}

backup, err := jobspec.Parse(&buffer)

if err != nil {

return err

}

_, _, err = b.client.Jobs().Register(backup, nil)

return err

}

The nomad file is embedded using the Go embed package to store the .nomad file in the binary, so we still have a single artefact to deploy:

//go:embed backup.nomad

var backupHcl string

And the backup.nomad file itself is a go template with custom delimiters ([[ and ]]) for fields, as the .nomad file, can contain {{ }} when using the inbuilt templating for populating secrets, amongst other things:

job "[[ .JobID ]]" {

datacenters = ["dc1"]

type = "batch"

periodic {

cron = "[[ .Schedule ]]"

prohibit_overlap = true

}

group "backup" {

task "backup" {

driver = "docker"

config {

image = "alpine:latest"

command = "echo"

args = [ "backing up [[ .SourceJobID ]]'s [[ .TargetDB ]] database" ]

}

env {

PGHOST = "postgres.service.consul"

PGDATABASE = "[[ .TargetDB ]]"

AWS_REGION = "eu-west-1"

}

}

}

}

Testing (Manual)

The great thing about developing against Nomad is that testing is straightforward. We can start a local copy by running nomad agent -dev, and then run our application locally to check it works properly, before needing to package it up into a Docker container and deploying it to a real cluster. It also doesn’t need to be packaged in a container for Nomad; we could use Isolated Exec or Raw Exec too.)

There is a start.sh script in the repository which will use tmux to start 3 terminals, one to run a Nomad agent in dev mode (nomad agent -dev), one to build and run the operator (go build && ./operator), and one to register and deregister nomad jobs.

When all is ready, submit the example job with the following command:

nomad job run example.nomad

Will cause the following output in the operator’s terminal:

==> JobRegistered: example (pending)...

Registering backup job

Backup created: backup-example

--> Done

==> JobRegistered: backup-example (running)...

Job is a backup, skipping

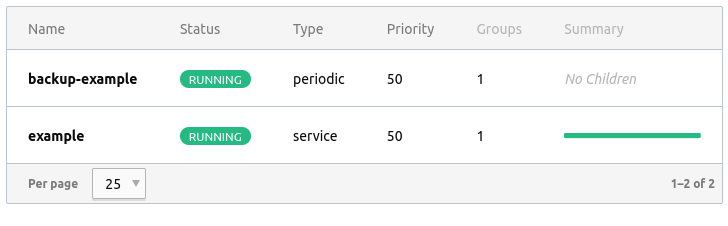

We can also check the Nomad UI, running on http://localhost:4646, which shows our two jobs:

Note how the example job is a service, which continuously runs, and the backup-example is a periodic job, scheduled to run daily.

Removing the example job with the following command:

nomad job stop example

This will be seen by the operator, which will remove the backup job:

==> JobDeregistered: example (running)...

Trying to remove a backup, if any

==> JobDeregistered: backup-example (dead)...

Job is a backup, skipping

Note how it also sees the backup-example job being deregistered and ignores it as, in our case, backups don’t have backups!

Testing (Automated)

We can also write automated tests in two ways for this operator; Tests that run against a saved or synthetic event stream, and tests that work in the same way as the manual test; start Nomad, run a test suite; stop Nomad.

Reading from a file of known events, we can test the handleEvent function directly:

seenEvents := []string{}

c := NewConsumer(nil, func(eventType string, job *api.Job) {

seenEvents = append(seenEvents, eventType)

})

for _, line := range strings.Split(eventsJson, "\n") {

var events api.Events

json.Unmarshal([]byte(line), &events)

c.handleEvent(&events)

}

assert.Len(t, seenEvents, 2)

assert.Equal(t, []string{"JobRegistered", "JobDeregistered"}, seenEvents)

}

The other way of testing is running a nomad instance in dev mode next to the application and registering jobs to it. Usually, when doing this, I would start the Nomad application before running the tests and then stop it after, to save the time of waiting for Nomad to start between each test:

wait := make(chan bool, 1)

client, err := api.NewClient(&api.Config{})

assert.NoError(t, err)

seenJobID := ""

c := NewConsumer(client, func(eventType string, job *api.Job) {

seenJobID = *job.ID

wait <- true

})

go c.Start()

//register a job

job, err := jobspec.Parse(strings.NewReader(withBackupHcl))

assert.NoError(t, err)

client.Jobs().Register(job, &api.WriteOptions{})

// block until the job handler has run once

<-wait

assert.Equal(t, *job.ID, seenJobID)

As this is running against a real copy of Nomad, we need to wait for jobs to be registered and only stop our test once things have been processed; hence we use a bool channel to block until our job handler has seen a job.

In a real test suite, you would need to make the job handler filter to the specific job it is looking for; as this would prevent shared state issues (currently this will stop after any job is seen), and thus allow you to run the tests in parallel.

Deployment

No operator pattern would be complete without pushing the operator itself into the Nomad cluster, and while we could just run the binary directly in Nomad (utilising the Artifact Stanza and Isolated Exec), its probably easier to create a docker container.

We have a single Dockerfile with a multistage build so that our output container only contains the binary itself, rather than all the layers and intermediate artefacts from the build process:

FROM golang:1.16.10-alpine3.14 as builder

WORKDIR /app

COPY go.mod go.sum ./

RUN go mod download

COPY . ./

RUN go build

FROM alpine:3.14 as output

COPY --from=builder /app/operator /usr/local/bin/operator

Once the container is built and tagged:

docker build -t operator:local .

We can verify it works as intended by running the container directly; --net=host is passed to the run command so that the operator can connect to Nomad on localhost:4646, rather than having to pass in our host IP through an environment variable. If you want to do this, add -e NOMAD_ADDR=http://SOME_IP_OR_HOST:4646 to the docker run command:

docker run --rm -it --net=host operator:local

Assuming we’re happy, we can run the Operator container in our local Nomad instance without pushing it:

task "operator" {

driver = "docker"

config {

image = "operator:latest"

}

template {

data = <<EOF

{{ with secret "nomad/creds/operator-job" }}

NOMAD_TOKEN={{ .Data.secret_id | toJSON }}

{{ end }}

EOF

destination = "secrets/db.env"

env = true

}

env {

NOMAD_ADDR = "nomad.service.consul"

}

}

Wrapping Up

The Operator Pattern is a great way to handle everyday tasks that a cluster operator would normally, and I have used it to handle things like automatic backups, certificate generation (at least until Vault supports LetEncrypt), and job cleanup (for example, developer branch builds only stay in the cluster for 3 days.)